Loading...

9th March 2021

It’s five years since we wrote our inaugural investment letter, Eternal Adaptation. In it, we cited the corporate mantra of one of our first investments, a packaging company called Sonoco, “Change is an immutable law: eternal adaptation is the price of survival”. While many in the investment management industry consider a “buy and hold” investment philosophy to be a badge of honour, we believe it neglects the reality of economies and markets. As this thirty-year history of the US market shows, industries wax and wane, some arrive afresh and others disappear for good.

Moreover, as we wrote in Revival of the Fittest (2016), companies are living faster and dying younger. The average tenure in the S&P500 in 1960 was more than sixty years, today it’s closer to ten. Moreover, the concentration of cash flow amongst just a few companies is stark and the companies earning that cash flow are changing ever-more quickly. Between 2000 and 2015 less than 60% of companies in the top fifty by cash flow managed to stay there the following year. The odds, on that basis, of staying in the top-fifty cash earners for the whole fifteen years was 2,700:1 against. One should be more attentive than ever to a rapid change in fundamentals.

The lesson is simple but often neglected. Buy-and-hold is a comforting mantra, adapt-to-survive is more realistic.

As the chart shows, technology has been the biggest show in town for many years. In recent weeks, there’s been some reversal – the “old economy” heavy Dow Jones Industrial index has outperformed the tech-heavy Nasdaq by 11% in the last month for example. Does this mark a long-term change in market leadership? Possibly. If it does persist then we, at least, will adapt to the new regime.

21st August 2020

“He spoke with a certain what-is-it in his voice, and I could see that, if not actually disgruntled, he was far from being gruntled.” P.G. Wodehouse, The Code of the Woosters

Most media I read and hear these days talk about these “unprecedented times” as if none of what we witness today has been seen before.

I wonder if its more to do with language than reality though. Some words just work well in pairs when it comes to describing events - unforeseen circumstances, unchartered waters - but precedented times, for some reason, doesn’t have the same ring.

As George wrote a couple of years back in The Anxiety Machine – The end of the world isn’t nigh, the tendency of the press to report news in an overly dramatic fashion, generally with a strong negative bias, is natural. As humans, we suffer a powerful cognitive bias towards overly dramatic, overly negative narratives. We have evolved to survive and so will always be more attentive to threats than good news. It is only natural, therefore, for the attention hungry media to focus on negative stories during these “unprecedented times”.

Although the combination of events in 2020 is unique, none of them on their own are materially different from anything we have witnessed in the last 100 years. A browse through the history behind our long-range US stock market chart (just scroll over the lines) reveals the never-ending barrage of fear which investors face. War, natural disasters, pandemics, mass unemployment, trade wars, debt fears, political crises, military coups, despots, and obsoletion all feature. So, however, does human endeavour, enterprise, new technology, global collaboration and the economic enfranchisement of huge swathes of the fast-growing global population.

The lessons from this simple chart are clear. Despite the news, stay invested for the long term and, whenever possible, re-invest dividends (click on the Linear button for the full effect).

None of what we see today is without precedent. For sure, we are witnessing an unusual cocktail of economic and political phenomena but perhaps they would be better described, in the spirit of P.G. Wodhouse, as merely a little less than precedented.

2nd February 2020

Within twenty-four hours of the Chinese authorities uploading the genetic code for the Corona virus to the internet, a San Diego based biotech company, Inovio, had digitally designed a vaccine and produced the first samples in its own lab. They started pre-clinical trials within a week and their vaccine, INO-4800, should to be tested on humans (assuming it’s found to be safe) by the early summer. Inovio is not the only company working on a vaccine - they are in healthy competition with, amongst others, Johnson & Johnson, Moderna Therapeutics and scientists in Australia.

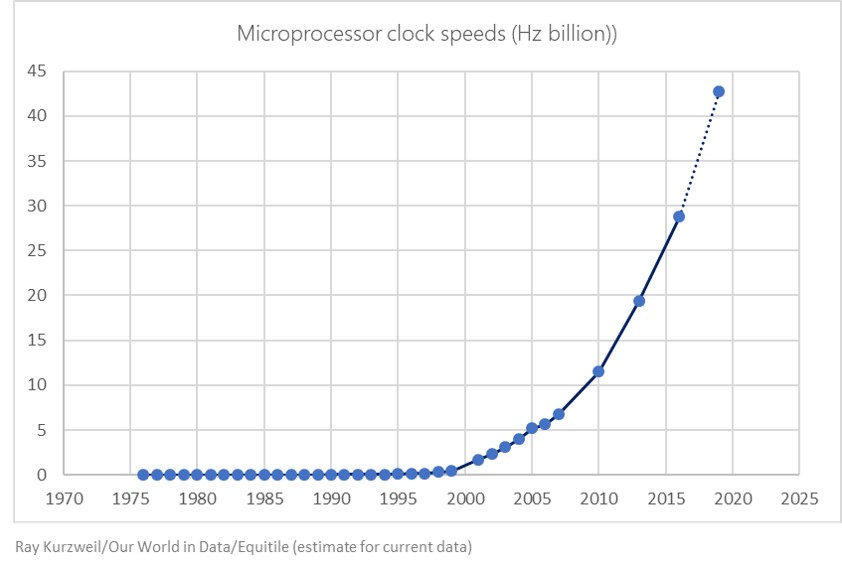

It’s a great example of how exponential growth in computing power is leading to a revolution in drug development. During the SARS outbreak in 2003 it took nearly two years before a vaccine was ready for human trials, for the Zika virus of 2015 this was down to six months – this time it will be a matter of weeks.

Digitally designed molecules to fight pathogens might look like the stuff of sci-fi but as processing speeds continue to double every eighteen months, the ability to design and test drugs without ever entering the lab is now normal.

I’ve been following the development of a US based private company, Schroedinger, which has industrialised molecule design on a grand scale. Whereas traditional approaches to drug discovery might have synthesized 1,000 compounds each year, Schroedinger’s platform can evaluates billions of molecules “in silico” per week with only the most promising molecules reaching the lab – some within the company’s own drug development programs. It’s not possible for us to buy shares in the company but their shareholder base is further testament to the convergence of computing power and bioscience – one of the company’s early investors was no other than Bill Gates.

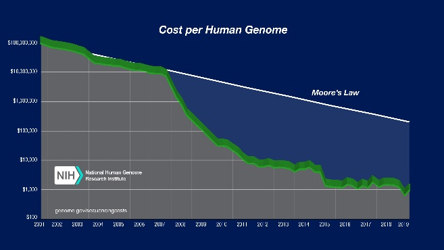

The connection between processing speeds and drug development is especially clear in genetic science. The cost of sequencing the human genome has fallen from $100,000,000 in 2001 to a little over $1,000 today. It’s no surprise, therefore, that patent filings for gene-based therapies are growing exponentially.

Whether a vaccine for the Corona virus will be available in time to stop it becoming a pandemic - or more likely before it burns itself out - is yet to be seen. The battle between silicon and pathogens, however, is in full swing.

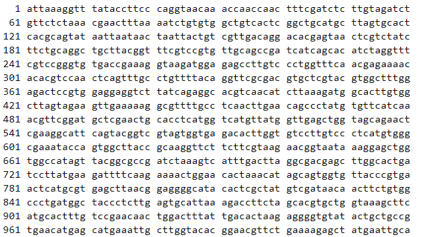

One can speculate on where this might lead. Along with ubiquitous computing power, smartphone health monitoring, home testing kits and so on, small companies and individuals can now innovate in a way that was previously the preserve of large corporations. And so, if there are any hobbyists out there who fancy their chances, here are the first 1,020 nucleotides out of 29,904 that make up the RNA of the Wuhan-Hu-Q. Good luck.